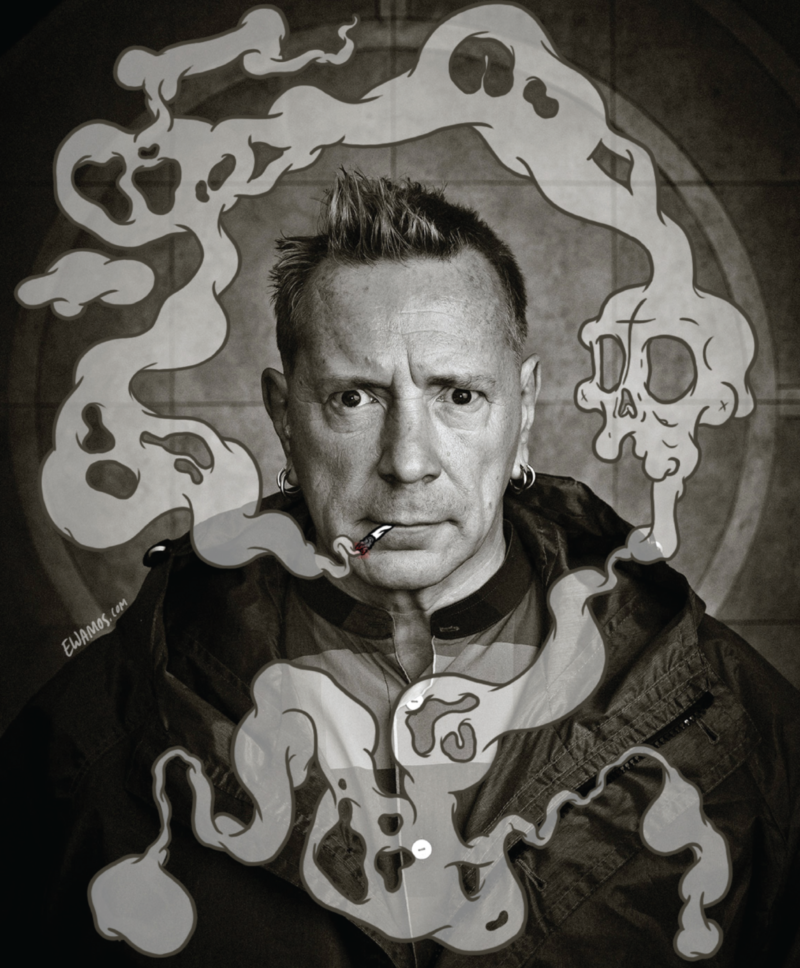

John Lydon’s voice is exactly how you’d expect; echoes of his sneering turn as the frontman of the most famous punk band in the world, bouncing through countless interviews derailed by his irreverence, and finally landing in a band of his own making. Public Image Limited, are a band defined as ‘post-punk’ conveniently enough because it defies any other genre description.

Lydon pounces on every question, starting his answers before I have even finished the question. I had many questions to ask him, most of which he ignored and spoke about whatever was on his mind anyway. But I was curious: How do you square being iconoclast when you become an icon yourself?

Well I suppose, you start by constantly still surprising everyone. When you’re held up as an anti-establishment idol, the most rebellious act you can do is appear in a butter advert. But I suspect John Lydon doesn’t think about these things, that butter advertisement paid for him to buy the rights of PIL back from Virgin. True freedom isn’t just doing what you want when you want; freedom is doing what you want without having to worry about the consequences. Doing the research I’d seen the bodies of journalists he’s destroyed in the past, understandably I was nervous.

John: Hello, Bunty of the Grange here.

Fused: Hello, Mr Lydon?

J: Oh no, it’s Bunty, honest.

F: Hello Bunty, is Mr Lydon there at all?

J: Hello! You called me Bunty, ha ha how sweet. Good morning. Ok, let’s get it on.

F: How did it feel to get to get the rights back for Public Image Limited from Virgin?

J: It was everything. To be free from their clutches and to stand on my own two feet. To be responsible and make decisions that were taken away from me. And to be able to make music again without an overwhelming debt issue being held over me. FREEDOM! But freedom comes at a serious price. To run your own label now, which we do, that’s 24-7. Major work to do it, but ultimately completely rewarding.

F: How would you feel being a young artist in the music industry today?

J: I think it would seem almost impossible. The truth is there are really no large labels left, they’re really just accounting firms. The thought of starting afresh independent with zero cash flow is overwhelmingly impossible. Now there’s lots of kids bouncing about with electronica all over the internet offering their two bob’s worth, but that’s all it amounts to, two bob. Because there’s nobody to pay you. It’s almost like the death of music. The record companies allowed it to happen; they killed the very thing they were parasitically earning off by not seeing what the internet’s threat was way in advance. All manner of accessing people’s music now without paying for it, with no one thinking “why would people be doing this for nothing?”, or to be out of pocket. Sure the love and joy of it all, but you’re limited.

F: What do you think the music industry needs to do to keep going?

J: I don’t know! I’m facing this myself, it cost me an awful lot to get off the labels and the only source of income is live tours. So we tour relentlessly and endlessly.

F: How’s that going, does that get easier?

J: It’s going fantastic, we avoid the very large venues and all the entrapments that come with that, and play small lovely warm intimate venues. Hopefully that will inspire a number of young fans to get out and hit the boards themselves. That’s another alarming thing about the music industry is that it’s not helping keeping these pubs and clubs and small theatres open.

F: That does seem like a problem.

J: It’s a serious problem. And nobody will know how to do anything, because it’ll all be done electronically for us, and that just isn’t very heartwarming for the future? I’m lucky to come from a time when things were done real. What you can see in the charts, what we’re being offered in the charts is manufactured pap. And it’s all stolen from people like mine’s work from way back when, with not so much as a thank you.

F: Come on though, can you really say that music today is much worse?

J: You can always moan about the current trends, it’s always been possible, but it seems at the moment that there’s a sad ending to it. I don’t want live music to cease; I don’t want it to end up as all Las Vegas fake performances by the chosen few bands that the industry supports. You look at the Grammys now and it’s the same bunch of Taylor Swift’s, it’s appalling. There’s no variety there. It’s sad to say I can put Jay-Z in there with all the other circus acts and I’m underwhelmed. They all require enormously expensive light shows, dancers and whatever gadgetry and trick they can to befuddle the viewer. But I would never call any of that a live performance, there’s too much mime going on. It’s like a very poor imitation of reality. Reality is nitty-gritty, up close and personal, this is very distant stuff.

F: Do you think music with passion and reality is due a comeback, just like British punk was a reaction to an oppressive government?

J: [Laughs] There’ll always be a youth culture; it’s just at the moment youth culture seems to be a bit hoodwinked, and the vast majority fell into the hip hop trap, which is all about purchasing corporate labels. Nike pops to mind, but whatever, basically conning people into thinking they have to pay outrageous prices for duff clothing that is manufactured in Korea. There’s no Do-It-Yourself in it, and that’s a let-down. As for rap itself, I can’t bear being shouted at. Enough. Alright. Already. Pop music seems to be massacred by things like X-Factor, American Idol; they’ve turned the wonderful world of live performance into karaoke.

F: Have you been back to Britain since Brexit?

J: Well wasn’t that a fascinating thing? That went on when I was there. No one was being offered any intelligent advice about what was being offered, what ‘in’ or ‘out’ meant. From either Labour or Conservative, and everybody seemed unsure about which way they were really going. I watched Boris Johnson’s face the next morning and he was more surprised than anyone that it went his way. I just don’t know if it’s going to make a great deal of difference to Britain. Britain, or England anyway, was just alone, it was definitely losing it’s identity in the European market. And that’s not good, not good at all. So where do I stand? I go with a ‘good riddance to Europe’ and that’s going to make touring for me very difficult in the future.

You can’t be controlled by outside sources, and that’s what being in the EU meant. Not knowing who they are, and not being able to complain to them or change anything, that’s ridiculous you can’t give up your rights. The ideology of being able to just say ‘no’ which was taken away from being in Europe. Wrong. Stop that. I know the Conservative Prime Minister at the time, whose name I won’t mention, went to the EU, and tried to make a change there, but they basically kicked him up the bum and sent him packing. And if anything I think that had the biggest impression on people in England, because that was it then. Sod ’em.

F: You described yourself as being ‘proud to be British’ in a couple of interviews, I was wondering what this means to you?

J: Well I’m proud to be a human being, and a member of planet Earth. I like different cultures and different approaches to life. It a wonderful thing to be able to see what human beings can come up with as different societies. That’s what makes travel enjoyable. I would not ever like to see one whole big shopping mall of a planet. Where everything was identical and we’re into the same things and we’re all being misled by the same lies; that would be very frustrating to me. It’s our difference what makes us special. So that’s my approach to it. Well done England, stand up for yourself !

F: As a writer, I’m always interested in people’s process, and you wrote two books, so how was that?

J: Well they don’t follow themselves chronologically; in fact the second one is based before the first one. I know that caused no end of confusion to the publishers but so what? I loved putting them together but it’s a very difficult and trying time to accurately remember situations, and to be able to speed write, well that’s something I wasn’t capable of. So I quickly turned to tape and then turned to friends to just help me. And it involved a journalistic approach with a tape recorder and some editing after.

F: Are there any more books in the future?

J: No doubt. I do find my life gets interesting. And I’m man enough to share that with you. It’s really a form of self analysis and you have to be ready to tell it as it is and a lot of personally hurtful things can come out of that, but at the same time it’s rewarding and refreshing to have dealt with them finally. The whole childhood illness thing, I’d kept that secret for most of my life and finally came to terms with it. I had meningitis and that’s an illness that nearly killed me, and nearly took forever away, not only my life but my memory. It took me four years to fully remember who and what I was. My parents were complete strangers to me; I might as well have been dropped off from a UFO. They were very cold and trying times. Very, very painful to go back into as it really was, but I did and it helped me so much with the last PiL album, songs like ‘I’m Not Satisfied’, came about because I started to analyse that period in song form. Because oddly enough I wasn’t satisfied, well, no one is, whether you’re ill or not.

F: Is all the art you make therapy for you then?

J: Writing songs are a form of therapy yeah. Putting songs together you’re trying to put landscapes together in your mind of the listener. And you want them to be as accurate as possible. It’s intense therapy because it’s intense work and the best therapy I’d recommend to anyone is HARD WORK. There’s no other way around it, and the harder the better. That’s a principal my dad instilled in me from a very early age.

F: My last question was going to be ‘do you have any message you would pass onto a younger John Lydon’ but does ‘hard work’ seem to cover it?

J: Yeah, to a very young Johnny I’d say: “carry on with the hair dyes and bleach because you won’t lose any hair for it, in fact the older you get the thicker your hair will get” and that’s the truth of it. I’ve put every chemical known to mankind on the top of my head, I should be bald as a peanut; it seems to have worked the opposite.

F: That’s a great place to leave it.

J: Maytheroadrisetomeetyou …mayyourenemiesalwaysbebehindyou… mayyouscatter flatterbutterandshutter.

The last bit he says in one giant breath, and hangs up. Not caring if I understood or not. I later find out it’s taken from a traditional Irish blessing, but, like everything with John Lydon whilst it seems simple it’s a little bit more complicated and nuanced than that. Despite his Celtic roots John Lydon is as English as grey Tuesdays, verdant hills, crisp packets in the gutter, and King Mob. And should the music industry and the whole of civilisation collapse tomorrow, I suspect John would still be there at the front of whatever makeshift stage, wild eyes searching for that connection.